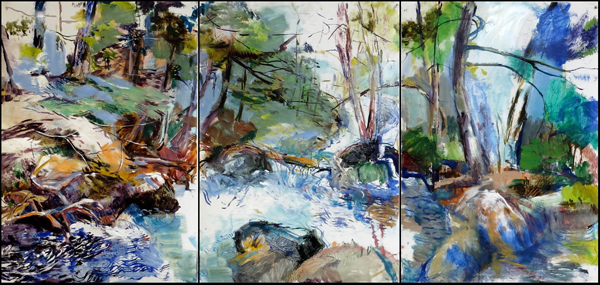

Maya Bar, Trees in My Mirror 2, 2008

Rooting Communities

Forest: November 4 – December 5, 2010

Entering a forest has a peculiar psychological effect on us since these dense arboreal spaces are both primal and strikingly eternal. Civilizations rely upon them for the most basic of materials, while forests also provide essential spaces that allow individuals to meditate upon the divide between nature and our constructed environment. They invoke a sense of timelessness that simultaneously lends urgency to our daily lives. Notable art critic John Berger weighed in that the temporal qualities of forests, “oblige us to recognize how much is hidden” (143).

In Canada, we take our temperate climate and densely forested landscape for granted. Our abundant ecological heritage is reflected in the artwork of the Group of Seven and the rich history of arboreal work at the core of Quebecois painting. Choosing to curate an exhibit of Israeli paintings and photographs titled Forest is fascinating in that it caters to our Canadian national aesthetic; however, these landscapes by Maya Bar, Anat Betzer, Dan Birenboim, Yehuda Porbuchrai, and Alina Speshilov are gravid with a hidden history of Israel, Middle Eastern politics, and foreign cultural significance.

The significance of trees is woven deep into the sociocultural fabric of Israel: from the near-mythic cultural memory of the lushly forested Promised Land described in the Bible to the fact that tree-planting provided jobs for the tides of mid-twentieth century immigrants setting foot on the barren Galilean ground they inherited when Israel was declared a state. As people from around the globe poured into this desert land, a fundraising campaign by the Jewish National Fund reached back across the oceans to buy the saplings necessary to revitalize the land. In the introduction to his seminal tome, Landscape and Memory, Simon Schama relates an awareness of the greening of Israel that began to percolate, tightening the national ties of this far-flung diasporic people.

All over North London, paper trees burst into leaf to the sound of jingling sixpences, and the forests of Zion thickened in happy response. And while we assumed that a pinewood was more beautiful than a hill denuded by grazing flocks of goats and sheep, we were never exactly sure what all the trees were for. What we did know was that a rooted forest was the opposite landscape to a place of drifting sand, of exposed brick and red dirt blown by the winds. The diaspora was sand. So what should Israel be, if not a forest, fixed and tall? […] Once rooted, the irresistible cycle of vegetation, where death merely composted the process of rebirth, seemed to promise true national immortality. (5)

As we can see from Schama’s carefully wrought anecdote linking afforestation to hopes for the future of Israel and a burgeoning local and global nationalism, Israeli artists who choose trees and forests as their subject are—often unintentionally—caught in the net of a larger ecological, ethnic, and political dialogue. Over sixty years of aggressive afforestation campaigns have transformed a denuded country of five million trees into one boasting over 200 million, spread over 225,000 acres of land. Moshe Rivlin, world chairman of the Jewish National Fund emphasizes the link of national sentiment to trees: “In most countries people are born to forests, and forests are given to them by nature. But here in this country… if you see a tree, it was planted by somebody” (Lora 1). Trees are planted wherever civilian and military settlements arise in order to provide social recreational space, anchor the sandy soil and buffer searing desert winds. From a global viewpoint, Israel’s ecological agency is astonishing: at the end of the twentieth century Israel was the only country in the world that emerged with more trees than it had at the beginning (Stemple 16). It is no wonder that the youngest contributor to Forest, photographer and video artist Maya Bar, is fascinated by a landscape that evolved and matured alongside her generation. As each year passed and childhood resolved into adulthood, the rows of young trees and oases of limans swelled into forests and groves which mapped the profusion of Israel’s settlements, delineated her borders, and altered the faces of her cities.

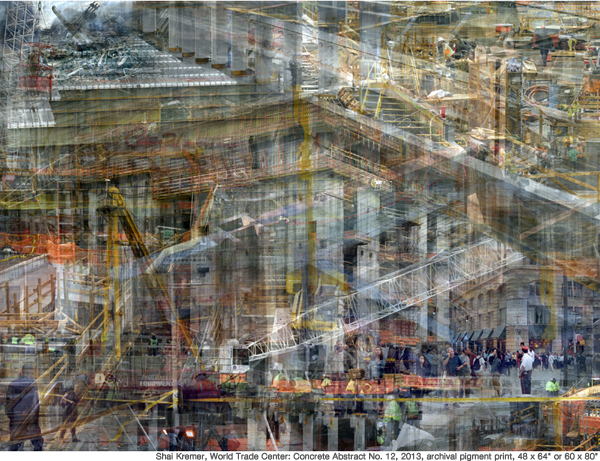

Born in 1979, Maya Bar lives and works in Tel Aviv-Jaffa, which is among Israel’s greenest cities. Forest is her inaugural show in Canada and focuses on one of her most prevalent bodies of work, which records copses of trees either through mirrored reflections captured in still photographs or using heavily edited kaleidoscopic video. Her signature is a fragmented, fractal quality or vibration that patterns the work, invoking a state akin to delirium. Toronto poet Alayna Munce described that gentle frisson of unreality within the forest as a “generous and double-jointed vision of time,” while Maya Bar chooses to describe it as the “unconscious of the ordinary.” The doubling and layering of the image amplifies the young, sinewy forests of Israel into a profusion of trees—projecting forward in time to envision a future landscape.

When Simon Schama was still a child in London, he was one among millions of diasporic Jewish people dispersed outside of their homeland and living as a minorities who anticipated these future forests, dutifully collecting the funds that would enable the crucial transformation of Israel into a living, habitable landscape. The planting of trees was and remains a nationalistic, culturally affirming action undertaken daily by scores of tourists, and emphasized by the state holiday Tu B’Shevat, The New Year of the Tree. However, with each step forward in the Middle East come consequences: the trees and forests of Israel are rooted within the complex political tensions of this volatile region. Annual rainfall is so minimal that each planting is an engineered event, and the act of sustaining the life of a single tree is implicated within territorial claims. This has led to antagonism between the JNF and the Bedouins, who feel that the greening program is a delegitimization strategy forcing them to cede their traditional nomadic way of life. Similarly, the JNF has come under fire for its use of afforestation to efface vestiges of former Arab villages and to enforce the country’s unstable border. Ilan Pappé, an Israeli historian from the University of Exeter in England, argues that, “The ‘green lungs’ of Israel have been created as part of the colonization of the country and the dispossession of the Palestinian people…” (Rinat & Aburawa). Though opinions differ radically in this incendiary debate, trees are irrefutably demarcations of ownership in a landscape torn by wars fed by territorial dispute.

Due to the unsavory shadow cast by land-claims, Israeli arboreal artworks betray a darkness; yet they are inherently optimistic. Though every work in this exhibit was created in Israel, several do not depict Israeli forests at all, but are born of imported nostalgia and memories of foreign political and ecological landscapes. Dan Birnenboim and Yehuda Porbuchrai each lived in New York City and though their techniques and the scale of their work differ, they share the choice of purely black and white pigments. Paintings of trees constitute an important vein coursing through both artists’ oeuvres. For Birenboim, who studied architecture at Pratt, the subject of forests is meshed with a dialogue of the greening of urban space, or the forest as a “green lung”—exemplified by New York’s Central Park. His trees are realistic, often set against a still, stark white ground to emphasize his impeccable control over the rich mercury pigment. In “Land of Shadows: Dan Birenboim”, Neomi Shalev argues that through the radical essence of black and white, “Birenboim discusses, inter alia, Israel’s internal politics: extremist conduct, rash definitive decisions, […] and the lack of a moderate, compromising alternative.” She continues, “At the same time, the forest may represent a trap; a dark, mysterious, tangled locus, an ideal place for dangerous and endangering activities” (32).

Yehuda Porbuchrai, who has been exhibiting internationally since the late 1970s, is recognized for his massive, intensely worked surfaces and unconventional choice of materials. Working on industrial sackcloth canvas, his methods have been described by Professor Mordechai Omer as a “direct continuation of tachist-conceptual tendencies” reflecting a tactile approach: paint-covered finger-marks sweep across the surface, disturbed by monochromatic scratches and scrapes that disfigure the image (44). Writer Adam Baruch conceptualizes the work as a “soot-covered map which the artist tries to reconstruct,” further embedding the work in the realm of landscape (43). The importance of the imported memories of forests which Porbuchrai and Birenboim carried back with them to Israel cannot be underestimated: the spaces they paint are inherently foreign to their native country. As such, not only do images of forests represent maps of settlements within Israel, they also trace the contemporary diasporic impulse of Israelis who choose to live abroad during their artistic careers. Despite the return to the “homeland”, there is a struggle to reconcile the nomadic history of the Jewish people with a rooted locale—particularly one in which military service is not a choice, but a difficult fact of life. Images of forests by Israeli artists are engraved with hope for a peaceful and abundant future landscape.

The impulse towards a high contrast canvas and impressions of stillness and nostalgia are carried on in Anat Betzer’s paintings of dark, ancient deciduous forests. Her heavily wooded landscapes clearly reference a Romantic lineage, informed by her time in England. Betzer alone introduces colour—though blacks invariably dominate. Unlike those native to Israel, her forests are chillingly desolate, yet pregnant with time. They connect intimately with John Berger’s writing on the subject:

What is intangible and within touching distance in a forest may be the presence of a kind of timelessness. […] In the silence of a forest, certain events are unaccommodated and cannot be placed in time. Being like this, they both disconcert and entice the observer’s imagination: for they are like another creature’s experience of duration. We feel them occurring, we feel their presence, yet we cannot confront them, for they are occurring for us somewhere between past, present and future. (144)

Alina Speshilov’s paintings also exist within artificially collapsed time, originating from childhood memories of the Siberian birch forests of Russia. Her canvases read like archetypes and balance precariously between technical prowess and childish naiveté. As with Betzer, Speshilov casts her imagination deep into the heart of the forest, maintaining a human scale by floating the graphic trunks of birch trees on a receding grey ground, never once betraying a hint of sky.

Viewing Forest is a culminative experience that interlaces the importance of memory, mapping and Diaspora evident in its artworks. For Canadian viewers, it offers an opportunity to reflect on our landscape—its influence on Canadian art and a national aesthetic—as well as providing insight into cultural spaces vastly different from our own. Contemporary landscape’s link to Diaspora is especially relevant to Canada considering that, like Israel, we are also a young country replete with immigrants whose experiences include drastic juxtapositions of natural environments, cultures, languages, value systems, and faiths. Let us return, finally, to Simon Schama, and consider the thesis of Landscape and Memory. He asks,

…if a child’s vision of nature can already be loaded with complicating memories, myths, and meanings, how much more elaborately wrought must be the frame through which our adult eyes survey the landscape. For although we are accustomed to separate nature and human perception into two realms, they are, in fact, indivisible. Before it can ever be a repose for the senses, landscape is the work of the mind. Its scenery is built up as much from strata of memory as from layers of rock. (6)

By Leia Gore, 2010

Emerging art writer & cultural critic from Toronto.

Works Cited

Aburawa, Arwa. “JNF Plants Trees to Uproot Bedouin.” The E.I. Oct 18, 2010.

Baruch, Adam. Yehuda Porbuchrai: The Plain Sense, A Selection of Works 1994-1997. Exhibition Catalogue. Tel Aviv Museum of Art. 1997.

Berger, John. “Looking Carefully—Two Women Photographers”, Hold Everything Dear: Dispatches on Survival and Resistance, Vintage Books, New York: 2007.

Lora, Mary Elaine. “Israel: A National Passion for Trees”. American Forests. FindArticles.com. 16 Oct, 2010. <http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m1016/is_n7-8_v96/ai_9200715/>

Munce, Alayna. “At the Palace of Versailles.” Presented at the AGO, ArtTalks. Sept 29, 2009.

Omer, Mordechai. “Forword.” Yehuda Porbuchrai: The Plain Sense, A Selection of Works 1994-1997. Exhibition Catalogue. Tel Aviv Museum of Art: 1997.

Rinat, Zafrir. “JNF using trees to thwart Bedouin growth in Negev.” Haaretz. Dec 8, 2008.

Schama, Simon. Landscape and Memory. Vintage Books, New York: 1996.

Shalev, Neomi. “Land of Shadows: Dan Birenboim.” Exhibition Catalogue. Museum of Israeli Art: 2007.